Eat, Pray, Take: Tortilla screen-printed with Hoisin Sauce at the Asian Art Museum’s Matcha event last Thursday. Click to enlarge. (Photo: Terrance Graven)

A week ago (7/26/12), one of our founding members served as special guest artist of The Great Tortilla Conspiracy, at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco’s monthly Thursday evening Matcha event.

This month’s Matcha was the culmination of a year-long “unofficial residency” project at the museum by artist Imin Yeh called SpaceBi. For this event, Yeh invited more than two dozen APA and local artists to participate, which is unprecedented in that it is close to two dozen more than are typically invited by the museum. (Action-packed event Program here)

The Great Tortilla Conspiracy was among those invited, and the Conspiracy in turn invited me as their special guest. Museum management was reportedly “thrilled” to learn of my participation.

As “The World’s Most Dangerous Tortilla Art Collective,” the Great Tortilla Conspiracy performs edible art-making by screen printing images onto tortillas, which are then served as quesadillas with salsa, free to the public.

For the Asian Art Museum event, we used Hoisin Sauce as edible “ink,” and provided kimchi as additional condiment, to create an “East meets South” fusion of art and food.

The Great Tortilla Conspiracy, Asian Fusion Edition. (Photo: Terrance Graven)

A museum visitor pulls a tortilla print

Quesadillas on the griddle

Consuming the Cosmic: Served with kimchi and salsa, satisfying complements to the cheese and hoisin. (Photo: Terrance Graven)

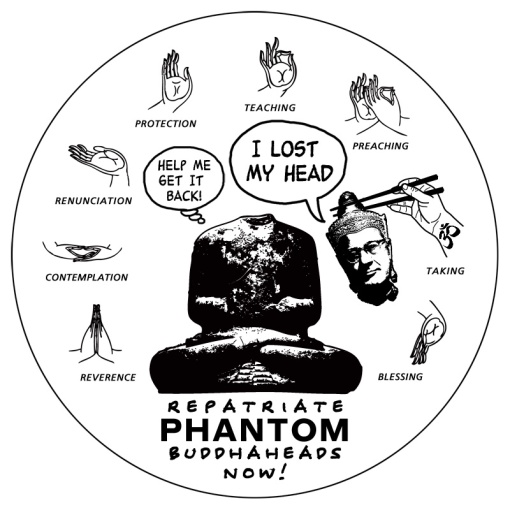

Original tortilla print design, in response to the museum’s PHANTOMS OF ASIA exhibit. How do you take contemporary art and make it retrograde? Force it into an essentialist frame of “traditional” (i.e. eternally fixed and unchanging) Asian cosmic spirituality, by combining it with antiquities from the permanent collection. This museum was originally founded by the City to house the largely unprovenanced Asian art collection of industrialist/imperialist Avery Brundage, who is pictured here as a severed buddhahead from his own collection (click to enlarge). (More information on flyer below.)

The Contemporary Trapped by the Past: actual text on wall at museum, reinscribes contemporary Asian within traditional Orientalist dichotomy of absolute, immutable difference from the West. “Ancient Oriental Secrets…”

Selling the Spiritual: “Ancient Oriental Wisdom” for sale at the museum gift shop, specially priced!

Hungry visitors queue up: do they know what they are consuming? (Photo: Terrance Graven)

Tortilla screen design by Imin Yeh. (Photo: Terrance Graven) A total of four designs by three different artists (Art Hazelwood, Yeh, myself) were printed, each design printed for an hour (sorry was too hectic to photograph all four).

Tortilla Design in response to PHANTOMS exhibit’s forced merging of contemporary art with a collection of sacred objects of largely unknown provenance, under the essentialist theme of cosmic Oriental “tradition”. (Click to enlarge.)

Kimchi was a hit. Note the flyer in hand (see below).

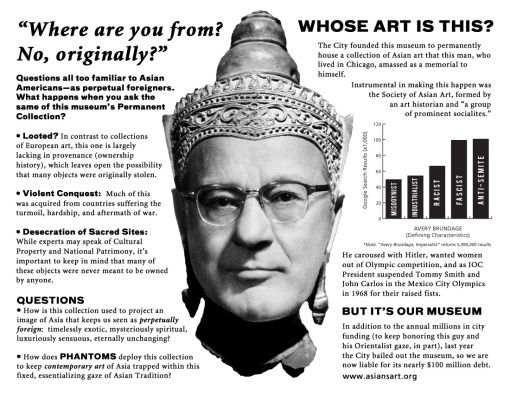

The Flyer: More information below about the Avery Brundage Collection and the man himself.

The Asian Art Museum was originally founded by the City of San Francisco to permanently house the Asian Art collection of Chicago-based construction and real estate magnate Avery Brundage, through a city bond measure approved by voters in 1960.

WHERE DID THIS ART COME FROM? How did it end up here? Under what conditions was it acquired?

- Looted? In contrast to collections of European art, the Avery Brundage collection of Asian art is largely lacking in provenance (ownership history) (as are other Asian art collections amassed by U.S. industrialists in the 20th century), leaving open the possibility that many objects were originally obtained through looting, stealing, or other illicit means.

- Violent Conquest: much of this collection was acquired from Asian countries suffering from the turmoil, hardship, and aftermath of war, as the U.S. became “the hegemon of East Asia”, conditions which made “superb” Asian art “available at reasonable prices.”

- Desecration of Sacred Sites: While experts may speak of Cultural Property and National Patrimony, it’s important to keep in mind that many of the objects in this collection were never meant to be owned by anyone. Despite international efforts at regulation, the world’s archaeological heritage continues to be “destroyed at an undiminished pace,” thanks to the lucrative market fed by demand from dealers, auction houses, collectors, and museums.

- Exploitive Collection Practices: Brundage’s practice of buying in quantity and exploiting art historians and curators has been criticized repeatedly [1, 2].

WHO WAS AVERY BRUNDAGE?

His connections to anti-semitism can be traced back to his university days, where he presided over a Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity chapter which operated with an official policy (emphasis added):

“In 1931, the fraternity’s National Laws stated that ’any male member of the Aryan race’ was eligible for membership, and provided that no person who has a parent who was ’a full-blooded Jew’ was eligible.”

As president of the American Olympic Committee, Brundage’s fraternization with Hitler and his emergence as the “preeminent American apologist for Nazi Germany” around the Berlin Olympics in 1936 are well documented. Shortly after Jesse Owens foiled Hitler’s intended demonstration of Aryan supremacy by winning four gold medals, Brundage suspended Owens from the AAU, an act which thereafter “barred Owens from competing in any sanctioned sporting events in the U.S.”

Two years after Brundage played an instrumental role in preventing a US boycott of the Berlin games, his construction company was awarded the building contract for the German Embassy in the United States because of his “sympathy toward the Nazi cause.”

By 1953, a year into a twenty year reign as president of the International Olympic Committee, Brundage came to favor the elimination of women from Olympic competition.

While he had no objections to the Nazi salutes at Berlin in 1936, Brundage reacted furiously when Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists at the Mexico City Olympics as they demanded, among other things, the ouster of Brundage as IOC president. Under Brundage, the IOC ordered the suspension of the athletes and spread rumors threatening to strip them of their medals.

Few were interested in examining why anyone would feel compelled to challenge an International Olympic Committee that coddled apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia, didn’t hire black officials or would be led by an avowed white supremacist and anti-Semite, Avery Brundage.—Dave Zirin, The Nation, June 2012

Why would an avowed racist collect Asian art? (See above, “Violent Conquest”). How do his white supremacist history, the lack of provenance of his collection, and the silence around both, relate to how this collection has been used to project an image of Asia that remains steeped in imperial ideology?

HOW DID HIS COLLECTION BECOME OUR MUSEUM?

An art historian from Mills College named Katherine Caldwell and “a group of prominent socialites” formed a Society for Asian Art in 1958 which convinced City Hall that Brundage’s collection was worth pursuing. The last Republican mayor of San Francisco then made “the avowed white supremacist” an honorary citizen of the city in 1959, and a bond issue was approved by voters in 1960 to house the collection that the “crypto-fascist” set up as a memorial to himself.

We’ll go out on a limb here and speculate that this Society of socialites was predominantly, if not entirely white. How much has that changed over the past half century, at a publicly-owned museum in a city whose population is one-third Asian? Whose needs are served by the Society for Asian Art’s narrow emphasis on “the concept of tradition” (i.e. Asian culture as essentially immutable) that is as static and fixed as Orientalism itself?

Can you imagine a Jewish Museum run predominantly by gentiles or a Mexican Museum without Latin@s?

How does the structural history of whiteness at this museum contribute to the persistence of its Orientalist gaze, and the Othering of Asian Americans in the Bay Area where we live? How much room is there for Asian and Asian American cultures as alive as our peoples, who cannot be contained by a romantic nostalgia for the Orient deeply rooted in a history of colonial power and imperial ideology?

WHOSE MUSEUM? OUR MUSEUM

In addition to providing more than $6 million for in annual public funding (pdf), the City bailed out the museum last year to the tune of a nearly $100 million debt for which we are now liable. Now, more than ever, we own this museum, and with ownership comes accountability.

(pdf), the City bailed out the museum last year to the tune of a nearly $100 million debt for which we are now liable. Now, more than ever, we own this museum, and with ownership comes accountability.

While we celebrate a Matcha event which included an unprecedented number of Asian American artists, we should also ask ourselves what kind of real structural institutional change it will take for the needs of our communities to be taken seriously, for us to play substantial roles that go far beyond event entertainment and gift shop window-dressing, to free us all from retrograde representations of Asian art and culture, to make the museum both relevant and viable in service of the communities who live here.

Decolonize the Museum: Invert the ⩝!

[…] together a larger group of artists to stage a series of interventions at the museum, including a day-long event that sought to expose and challenge the framework that the Asian Art Museum operates within. In […]